To mark the 60th anniversary of Batman premiering on ABC, and bringing Gotham’s live-action citizens into our living rooms, I thought I would celebrate by launching another Tour of the Solar System entry.

Sorry, what’s that? Did you just ask what the Batman TV show and the Solar System have in common? Absolutely nothing, of course. As a student of history, superheroes and space, what else was I supposed to do?

In other news, one of the world’s most sought-after projects is back for 2026! No, it’s not about Kim Kardashian’s new clothing line. No, it’s not about Alex Jones’ new “Anti-gay frog” cream. No, it’s not about a new Salt and Vinegar/Pizza chips variant, though that does sound amazing.

The truth is harder to accept, but the astronomy content that would never be introduced into schools and universities has returned! Yes, The Tour of the Solar System has returned! Yay, I mentioned it for a second time.

I know the world has either stopped taking its medication, or it needs to start, so it is forgivable if you have missed the thrilling entries of this project. The previous entries are:

1.) Meet the Family

2.) The Sun

4.) Mercury

5.) Venus

7.) The Moon

8.) Mars

10.) Ceres

11.) Jupiter

12.) The Galilean moons

13.) Saturn

14.) Titan

15.) The Moons of Saturn

16.) Uranus

17.) Titania

18.) The Moons of Uranus

19.) The Literary Moons of Uranus

20.) Neptune

21.) Triton

22.) The Moons of Neptune

23.) The Kuiper Belt

Our last tour stop brought us to the Kuiper Belt, so today’s lecture will be about one of the first denizens we are going to meet there: Pluto. We have a lot to discuss about this distant ice ball, where a not-so ancient grudge will hopefully not break into a new mutiny. Ladies and gentlemen, boys and girls, get ready for another awkward amateur academic attempt aimed at astronomy. Prepare thyself, for we are going to Pluto!

So, here we are at Pluto. Before we venture on, I need to address the grumpy elephant in the room. I’m going to say something that I’ve mentioned previously during this project, but it needs to be repeated. Pluto is not a planet, but rather a dwarf planet. Now, I’m going to leave that statement there to marinate, and we are going to discuss this later.

However, in the meantime, we are going to treat Pluto as a planet during this tour stop until the proper time when we are going to have an intervention. So, going forward, we are treating Pluto as a planet, until we don’t. Clear as mud? Awesome, let’s continue.

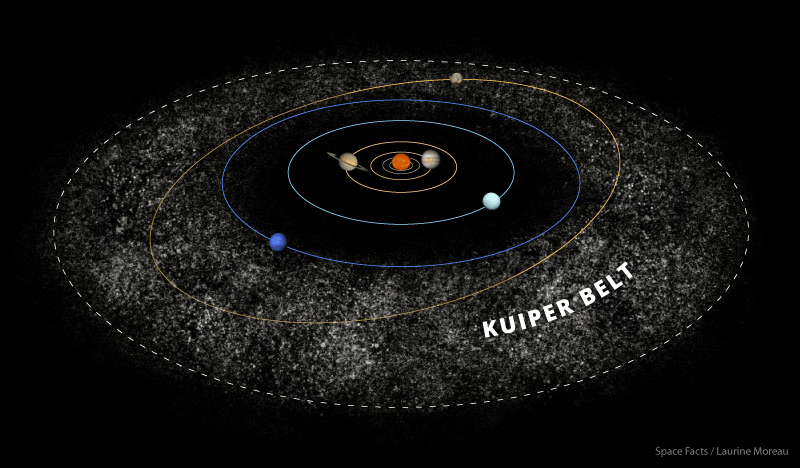

At best estimates, Pluto was formed 4.5-4.6 billion years ago, similar to the outer planets, or gas giants. Pluto is a Trans-Neptunian object (TNO) because it orbits the Sun at a greater average distance than Neptune, but it’s also a Kuiper Belt Object (KBO), because, you guessed it, it’s located in the Kuiper Belt.

Pluto’s name and its discovery are connected, but not in the traditional sense. If you can cast your mind back to Neptune’s tour stop, you will remember that Neptune was the first planet to be discovered through mathematics, as predicted by calculations based on observations of Uranus.

For years after Neptune’s discovery in 1846, scientists believed there was another planet, just waiting to be discovered, beyond Neptune’s orbit. This was because of the observations made of Uranus and Neptune. This undiscovered planet was named Planet X, coined by Percival Lowell. In hindsight, this was a pretty boss name, since science-fiction writers liked using it later on.

Anyway, scientists kept looking beyond Neptune with increasingly advanced telescopes and building new observatories, like the Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona, United States. It was founded by, wait for it….Percival Lowell. The job of finding Planet X at Lowell Observatory was handed to Clyde Tombaugh in 1929.

Using an astrograph, which is a telescope that can take photographs, Tombaugh spent his time taking photographs of various sections of space beyond Neptune and comparing them to detect movement. Eventually, this painstaking mission succeeded in the discovery of Planet X on 18th February 1930, after which the news was released on 13th March 1930.

When naming this new planet, the tradition was to give the planet a name from Roman mythology, but as you know, Earth and Uranus are the exceptions. The public’s response to the first planet to be discovered in 84 years, and the first in the 20th century, was to flood Lowell Observatory with names. Minerva, Cronus, and Pluto soon became the most popular.

As I understand the story, an Englishman, Falconer Madan, read about Pluto’s discovery in the newspaper to his family at breakfast. Listening to this was his eleven-year-old granddaughter, Venetia Burney. She suggested the name Pluto, taken from Roman mythology, as Pluto was the brother of Jupiter and Neptune. Pluto was the god of the underworld, and his Greek equivalent was Hades.

Madan worked at Oxford University, so he passed on the suggestion to Herbert Hall Turner, an astronomy professor, who, in turn, passed it on to the staff at Lowell Observatory. A vote was taken, and Pluto was declared the winner, with the name being published to the public on 1st May 1930.

Sorry, that was a long-winded explanation about Pluto’s discovery and name. I’ll try to be more concise, though I can’t make any promises.

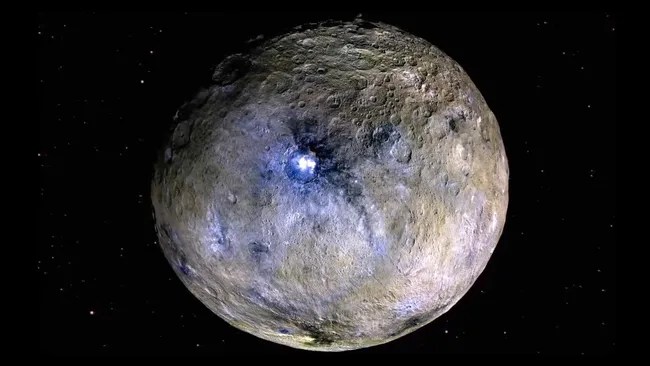

Pluto is a small world, as it’s even smaller than Mercury. It has a diameter of 2,377 km, which makes Pluto only about 1/5th of Earth’s width. Pluto is also smaller than the Moon; however, it is larger than Ceres. Size, like time, is relative.

Pluto’s orbit of the Sun can be quite staggering, along with the distance. We have mentioned this before, but many planets have elliptical orbits in the Solar System. Earth has one, even though it’s slight, we still have one. Pluto’s orbit, on the other hand, is out of control. Just ask the Chemical Brothers.

Pluto’s perihelion, which is its closest point to the Sun, is about 4.43 billion km, while its aphelion, the furthest point away from the Sun, is about 7.37 billion km. This means Pluto’s average distance from the Sun is about 5.9 billion km, and it has an average orbital speed of 4.743 km/s. It’s not a shabby speed, but the Millennium Falcon could still smoke it.

Like all of the planets past Jupiter, the Sun’s light will take a lot longer to reach each world because of the gigantic scale in distance.

Light from the Sun takes about 8 minutes and 20 seconds to reach Earth; in comparison, it takes 5.5 hours to reach Pluto. That’s the same amount of time you could watch Kill Bill: Volume 1, Kill Bill: Volume 2, and Army of Darkness back-to-back.

Pluto’s rotation is nothing to laugh at, because its rotation is part of its identity. One Plutonian day, which is the time it takes for Pluto to make one full rotation, is equal to 6.375 Earth days, which is 153 Earth hours. That’s intense.

As for a Plutonian year, the length of time it takes to make one orbit around the Sun, well, brace yourself because it is the equivalent of 248 Earth years. To understand what that time scale means, since its discovery in 1930, Pluto won’t make a full orbit of the Sun until 2178.

Also, 248 years ago, when Pluto was roughly in its present location in time and space, Captain James Cook and his crew became the first Europeans to visit the Sandwich Islands, later named the Hawaiian Islands; and the American Revolutionary War noted two key moments: the Treaty of Alliance was signed, and the Valley Forge encampment was in its second month. The slave population in the United States at the time equalled about 22% of the total American population, while the world’s population in 1778 was between 750 million and 900 million people.

I mentioned this fact while discussing Neptune, since it’s a very important piece of information about Pluto. It has an orbital angle of over 17°, relative to Neptune’s orbit. This is an oddity because it means, for a short amount of time, 20 years, compared to the universe, of course, Pluto goes inside of Neptune’s orbit.

The last time it happened was between 1979 and 1999. So, that meant from 1979 to 1999, Neptune, not Pluto, was the furthest planet in our Solar System. To make it even crazier than a wedding in Las Vegas, this 20-year cycle has started again, with Pluto currently inside Neptune’s orbit.

Pluto spins with a 120° angle relative to its plane of orbit around the Sun. That doesn’t mean much, until you learnt the fact that, similar to Uranus, Pluto spins on its side, as well as having a retrograde rotation. Pluto does enjoy being weird.

And speaking of being weird, since its axial tilt is so high, Pluto experiences seasons that last for centuries; Westeros has nothing on Pluto. In addition to this, because Pluto is billions of kilometres away from the Sun, the world would be the perfect holiday location for Mr Freeze. Temperatures range from -238°C to -218°C, averaging around -225°C. Seriously, that’s mad.

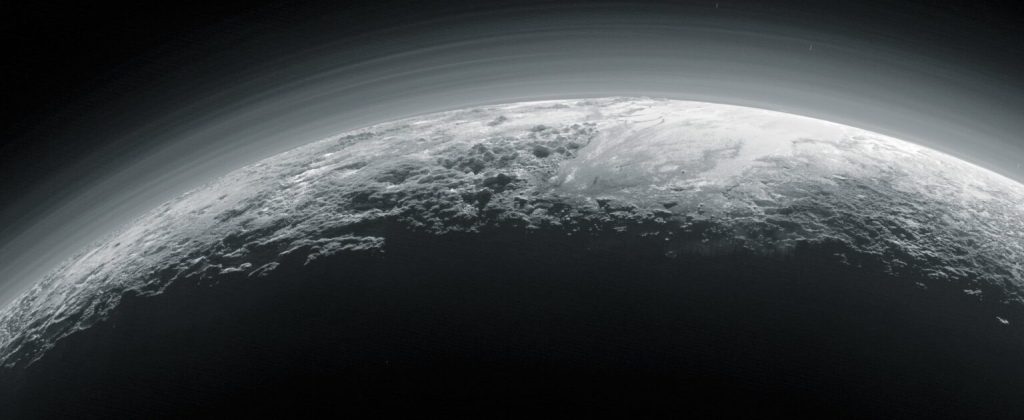

The thin atmosphere of Pluto is nightmare fuel as well, which consists of nitrogen, methane, carbon monoxide, acetylene, ethylene, and hydrogen cyanide. Life as we understand it would not thrive or survive on such an inhospitable cosmic creation.

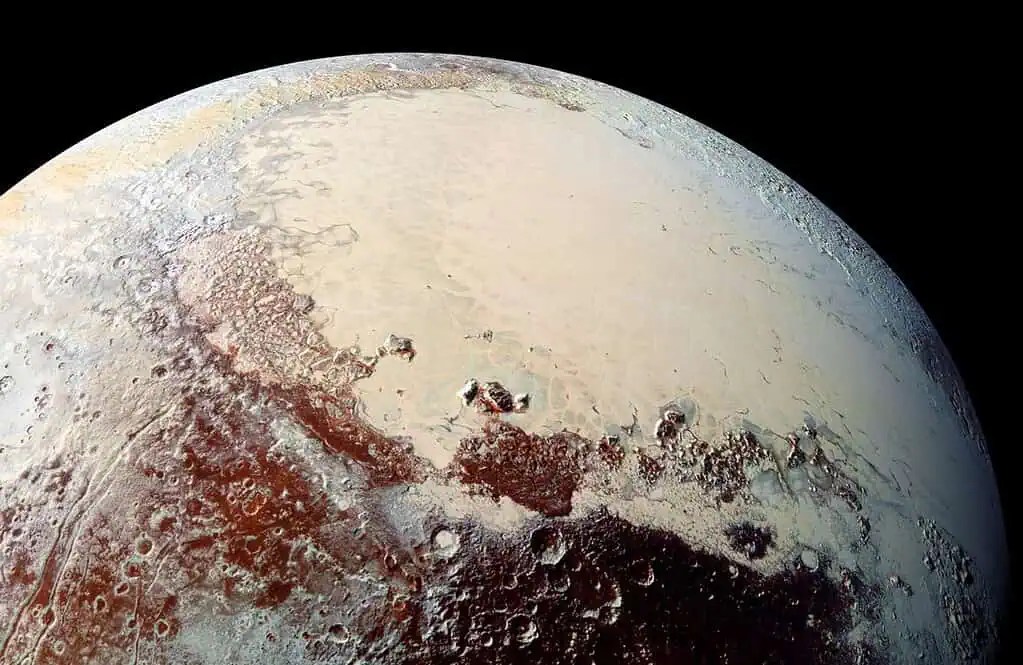

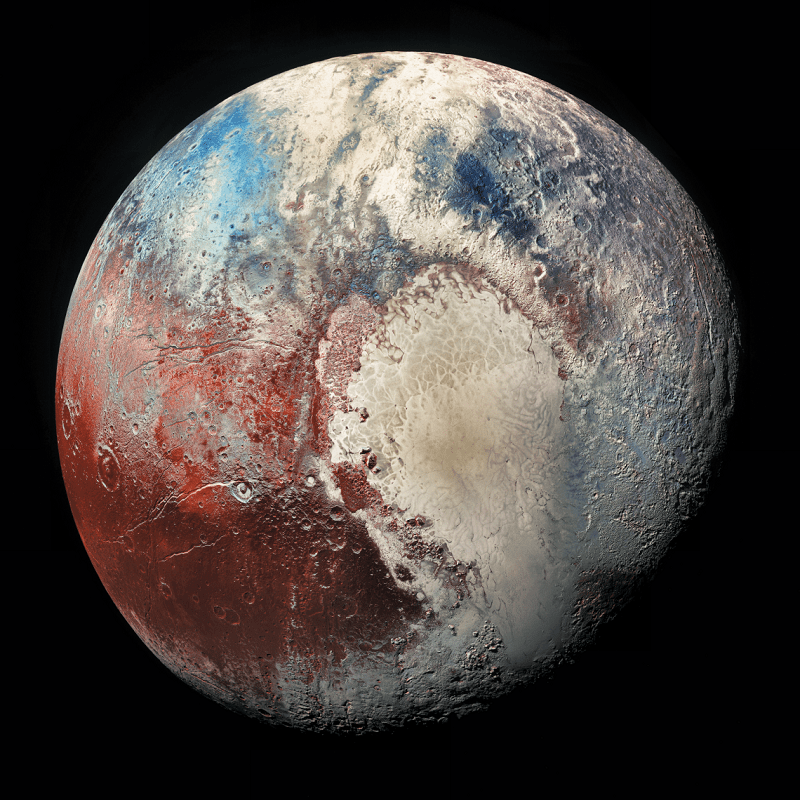

Even though Pluto is, for all intents and purposes, devoid of life, it still has some interesting features on the surface, which is littered with craters, valleys, plains, and mountains. It features names like Brass Knuckles, Wright Mons, Piccard Mons, Voyager Terra, Hayabusa Terra, Cthulhu Macula, Sputnik Planitia, Tombaugh Regio, and Al-Idrisi Montes. Pluto also has mountain ranges called Tenzing Montes and Hillary Montes.

Bonus points for anybody who can identify the origins of these fantastic names. New Zealanders and sci-fi fans have a small advantage, sorry.

We have reached the part of the tour stop, which can make certain worlds a little sensitive about the next two topics: rings and moons. Sadly, Pluto does not belong to the rings club, though Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune, Sauron, and the Mandarin are members.

As for moons, yes, Pluto is allowed into this VIP section of the Solar System. It has five moons, whose names are just as bad arse as Pluto’s features. Their names are Charon, Styx, Nix, Kerberos, and Hydra, but we will discuss them next time, since they are just as odd as Pluto. I love it.

It’s this part of the tour stop that I would present some quirky or interesting facts about Pluto. That being the case, there’s nothing more important than what I’m about to discuss. I’m sure if you cast your mind back to the start of this outrageous and boorish piece of science communication, we have been treating and discussing Pluto like a planet, but it’s really a dwarf planet. Correct? Great, let’s get into it.

This is another long-winded story, but I’ll try to jazz it up for you. Since Pluto was discovered in 1930, it had enjoyed being classified as a planet. It was in all of the textbooks, and you may have learnt about it at school, with the planet acronym, Mercury/Venus/Earth/Mars/Jupiter/Saturn/Uranus/Neptune/Pluto, which covered some hilarious mnemonic phrases.

However, not all scientists agreed that Pluto was a planet, mainly because of its size, since there were moons larger than Pluto, like Ganymede, Titan, Callisto, Io, Europa, Triton, and even our amazingly named moon, The Moon.

Another argument was about Pluto’s orbit, which, if you remember, cuts inside Neptune’s orbit. It was thought that planets should not be able to do this, so along with other arguments, there was a debate about Pluto’s planetary status.

Things changed in 2005, when a group of astronomers discovered a TNO and named it Eris. This new world was being touted as a possible tenth planet, but there was a problem: it appeared to be slightly larger than Pluto.

This presented the astronomers of the world with a problem: what do we call these small worlds like Pluto, Eris, Sedna, and even poor old Ceres, which are not moons? If they are not planets, what are they? They decided to solve the conundrum once and for all by having a meeting. A very special meeting.

Later that year, a group of 19 members of the International Astronomical Union (IAU) got together to discuss and sort this mess, and hopefully to come up with new planetary classifications and definitions. If Science were a Lego game, then the IAU would be in charge of astronomy and doing all of the digging to get those sweet mini-kits and studs. They did this by dividing the worlds into three groups: planets, dwarf planets, and small solar system bodies.

In the third tour stop, I discussed the differences between a planet and a dwarf planet. I mean, if you’re in a nightclub and you want to buy a world a drink, you want to know whether you’re doomed to fail with a planet or a dwarf planet; am I right? Different strokes for different folks.

I’m repeating myself here, but the IAU definitions of a planet are as follows:

1.) Is in orbit around the Sun.

2.) Has sufficient mass to assume hydrostatic equilibrium.

3.) Has “cleared the neighbourhood” around its orbit.

The first is obvious: the planet must orbit around the Sun.

The second talks about the planet achieving hydrostatic equilibrium, which is just a nearly round shape.

The third is about when a planet orbits the Sun; it must be the most dominant gravitational object in that orbit. It means the planet needs to be able to sling or clear the neighbourhood of any other smaller objects in its path.

Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune all meet these criteria. However, if we apply these criteria to Pluto, things get serious. It passed the first and second, but Pluto failed the third criterion, as it hasn’t cleared the neighbourhood in its orbit.

This was mainly because, once again, its orbit cuts inside of Neptune’s orbit. It also has a quirky orbital dance with Charon, one of its moons; and its location in the Kuiper Belt, as it is surrounded by other icy worlds.

Pluto’s status as a planet was revoked, thanks to the IAU swiping left. So if Pluto wasn’t a planet, then what was it?

Don’t panic, for the IAU was here to save the day, and to tidy up their own mess. Enter the brand new classification of dwarf planets, which had not three, but four criteria.

1.) It must orbit the Sun.

2.) Has enough mass to be round.

3.) Has not cleared the neighbourhood around its orbit.

4.) It must not be a natural satellite (moon).

When graded against these four criteria, the IAU swiped right on Pluto and was reclassified as a dwarf planet, along with many others. Ultimately, it meant that the bouncers let Earth, Ceres, Mars, Eris, Saturn, Pluto, and the rest into the nightclub, but once they were in, they divided the worlds into two separate rooms, so they could party and dance with their own kind. Buy one drink and get one free is always popular, especially on noraebang nights.

Yes, it seems cruel and petty to do this to Pluto, but in the pursuit of scientific accuracy, sadly, it needed to be done. I mean, it’s not like Pluto has feelings, right? Right?!

Anyway, it’s one of the reasons that Pluto and Eris don’t get along, especially after a few drinks. Poor Ceres has to play referee, and the Sun, the manager of the nightclub, just ends up threatening to kick both of them out if they can’t behave themselves.

It’s hilarious that Pluto blames Eris for the declassification/reclassification debacle, when in reality, it was Earth’s fault for demanding to talk to the manager. What a Karen move, Earth!

And that brings another thrilling episode of the universe’s least recommended astronomy project to a close. “Some Geek Told Me’s Tour of the Solar System is a masterpiece in science communication,” said no astronomer or astrophysicist ever.

What’s your favourite fact about Pluto? As always, please let me know. Thanks again for reading, following, and subscribing to Some Geek Told Me. If you don’t push your own boat, no one else will, so if you want to follow someone new, visit my wonderful, but dull Twitter and Mastodon, accounts.

Please don’t forget to walk your dog, read a banned book, continue watching videos where ICE agents slip on ice, and if you ever repeat any of the information I write about, and someone asks you where you learnt it, just say, “Some Geek Told Me.” I’ll see you next week for some rugby!

References:

NASA: Pluto Facts. https://science.nasa.gov/dwarf-planets/pluto

Wikipedia: Pluto. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pluto

You must be logged in to post a comment.