Welcome back to the most basic and cost-effective Tour of the Solar System you will ever see! It’s cheap and nasty, but it won’t make you visit the doctor. We’ve been on this tour for over a year now, so if you’re just joining us, here are the previous stops:

1.) Meet the Family

2.) The Sun

4.) Mercury

5.) Venus

7.) The Moon

8.) Mars

10.) Ceres

11.) Jupiter

Because you’re observant, you would have noticed the title of this blog, but let’s clear some things up first. The Galilean moons are not a cosmic STI, nor are they a new punk band from Berlin.

Jupiter has 95 officially recognised moons, but for this work of literary incompetency, I’m only going to be discussing four of them; Io, Callisto, Europa and Ganymede, the Galilean moons. If you remember from our last tour stop, I briefly mentioned them; and for me, briefly means five paragraphs. They’re gorgeous too!

Let’s step into our TARDIS of the mind, and travel back through time to Italy, around late 1609 and early 1610. Telescopes were a new invention, and a certain jack of all trades named Galileo Galilei decided to make his own version.

Not long after this, Galileo used his telescope to peer into the void and reveal things behind the curtain. He made some stunning discoveries and observed things like the Moon’s craters and mountains, the phases of Venus, sunspots, Saturn, and stars within the Milky Way. These discoveries have helped move humanity forward, in our understanding of space and our place in it.

However, Galileo’s biggest contribution to astronomy was the revelation that Jupiter had moons. That doesn’t sound like much, but I promise you, it was a colossal discovery. At the time, one of the main models explaining the nature of the universe was the Geocentric model; also known as the Ptolemaic world system.

Basically, this model suggested that the Earth was at the centre of the universe, and everything including the Sun, Moon, stars, and planets, would be orbiting the Earth. Sounds reasonable, right?

That all changed when Galileo observed something strange, using his new telescope. He noticed what he believed to be some fixed stars near Jupiter, but after weeks of detailed observations, Galileo concluded that these fixed stars were not fixed stars at all, because they were orbiting Jupiter.

Galileo had discovered moons orbiting a planet, just like the Earth and the Moon. This revelation supported the recent Copernican heliocentrism model, explaining that the Sun was at the centre of the universe, and planets like Mercury, Mars, Jupiter, and even Earth, revolved around it. The Galilean moons were also confirmed and discovered by Simon Marius, a German astronomer, around the same time.

In 17th-century Europe, this was a major scandal, and even heresy to support such an idea. But as you know, the Copernican heliocentrism model was proven correct. The Sun does not orbit the Earth; the Earth orbits the Sun.

As for the moons, they’re just like a team of rugby players; similar, yet different.

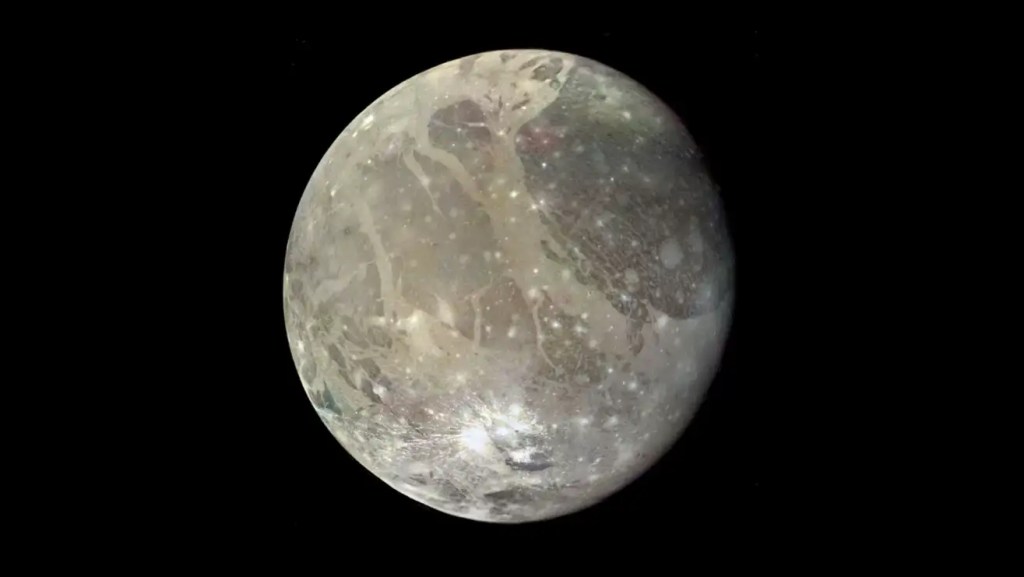

Let’s start with Ganymede, because you know, why not? Not only is Ganymede the largest of the Galilean moons, or the rest of Jupiter’s moons, but it’s also the largest moon in the Solar System. It’s even larger than Mercury.

Ganymede has a diameter of 5,270 km, and orbits Jupiter roughly at 1,070,400 kilometres; which is the third of the Galilean moons in distance from Jupiter. Ganymede also has a magnetic field, possibly due to its liquid iron core, and it takes roughly seven days to orbit Jupiter.

One of the most interesting discoveries about Ganymede is that it has a subsurface ocean. This is exciting because of the possibility of scientists finding life in the ocean. Granted if life exists on Ganymede, it would be in the form of microorganisms, but a win is a win!

Image: NASA

The next largest moon is Callisto, with a diameter of 4,821 km, and an orbital distance from Jupiter of 1,883,000 km. This makes Callisto the furthest of the Galilean moons to orbit Jupiter. Callisto is also one of the most heavily impacted objects in the Solar System, as it is riddled with very extremely old craters.

Because of its location from Jupiter, Callisto takes about 16 days to orbit the planet. Subsurface oceans seem to be the trend with the Galilean moons because Callisto is suspected of having one, but that has not been confirmed. Yet.

Our third-largest Galilean moon is so cool, it only has two letters in its name. Io has a diameter of 3,643 km, which makes it slightly bigger than our Moon at 3,475 km. Io orbits Jupiter at a distance of 421,700 km, which makes it the closest of the Galilean moons to Jupiter. Given its close distance, Io orbits Jupiter in just under two days.

Io can also take the title of having the strongest surface gravity of any moon and the highest density of any moon in the Solar System. Io is also quite odd because it has over 400 active volcanoes, in addition to having over 100 mountains; with several mountains reaching heights that are taller than Mount Everest.

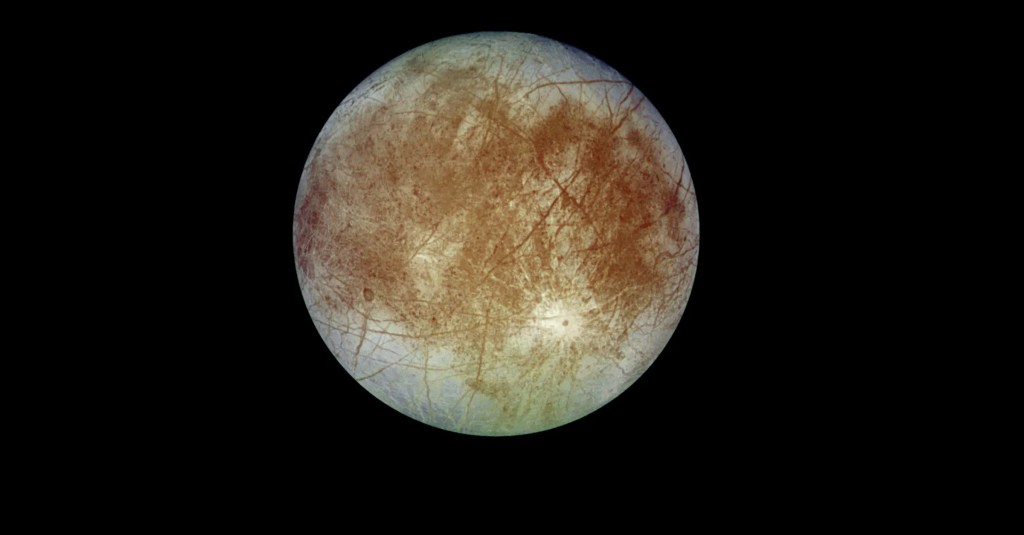

Europa is our fourth and final stop on this tour today. Orbiting at a distance of 670,900 km means Europa is the second closest of the Galilean moons to Jupiter, between Io and Ganymede. However, Europa is the smallest of the four, with a diameter of 3,121km.

Considering its close proximity to Jupiter, Europa orbits Jupiter in about 3.5 days, and it also appears to have an extremely smooth surface. In saying that, Europa is covered in dark lines called lineae. These are believed to be caused by interior processes, which has led to the theory that Europa could have a subsurface ocean as well.

There’s a lot more to the moons than what we have discussed, but I can’t do everything. Maybe. So, that’s it for today. The next stop on the tour will be a popular one for many people: Saturn. Just remember that the tickets for the tour are non-refundable.

Thanks once again for reading, following, and subscribing to Some Geek Told Me. I’m also on X and Mastodon because that’s where the cool people are. Please don’t forget to walk your dog, read a banned book, eat some lemons, and I’ll see you next week.

You must be logged in to post a comment.